|

Over the years whenever I stayed in the Kanto-area I spent the weekends visiting music shops, drinking coffee, anything to while away the lonely time spent away from home. How a homebody spent his career traveling internationally is another story, but let's just say that if it weren't for limited overhead luggage racks, Japan and a love of music I never would have found the ukulele or UkuleleJapan.com!

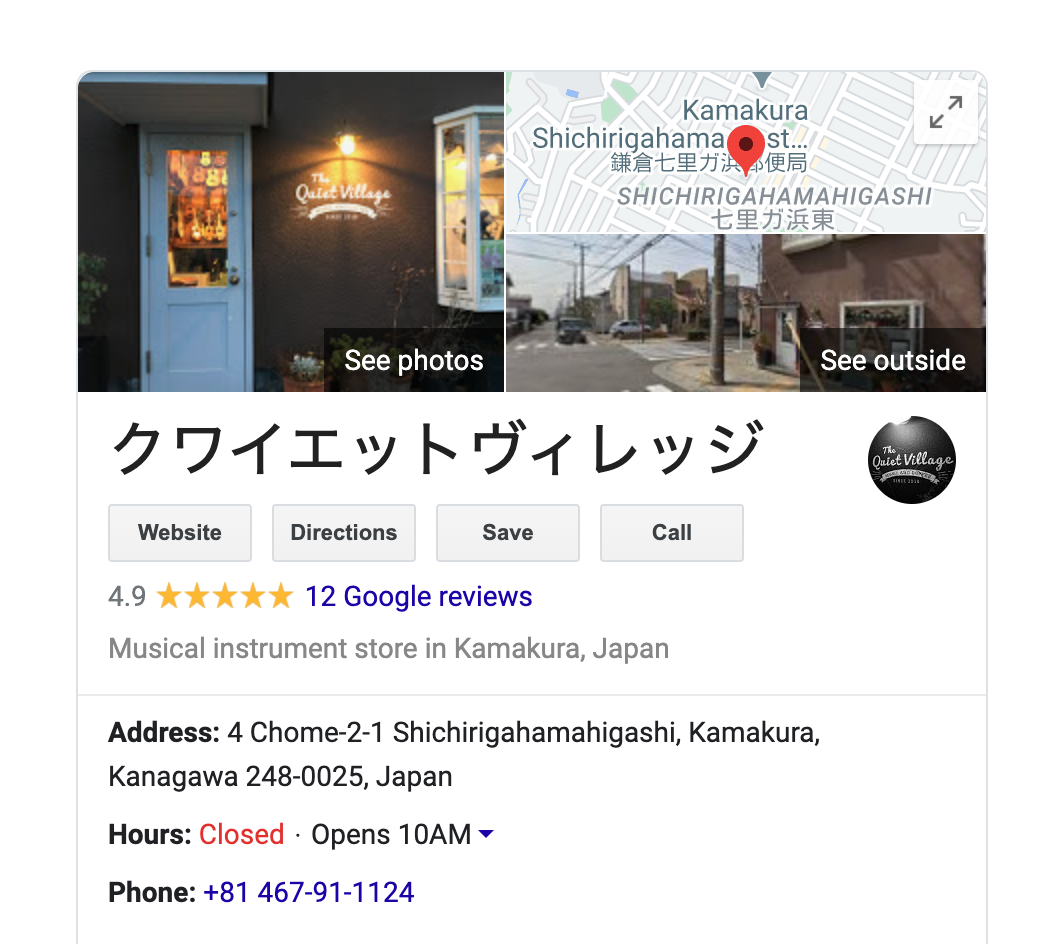

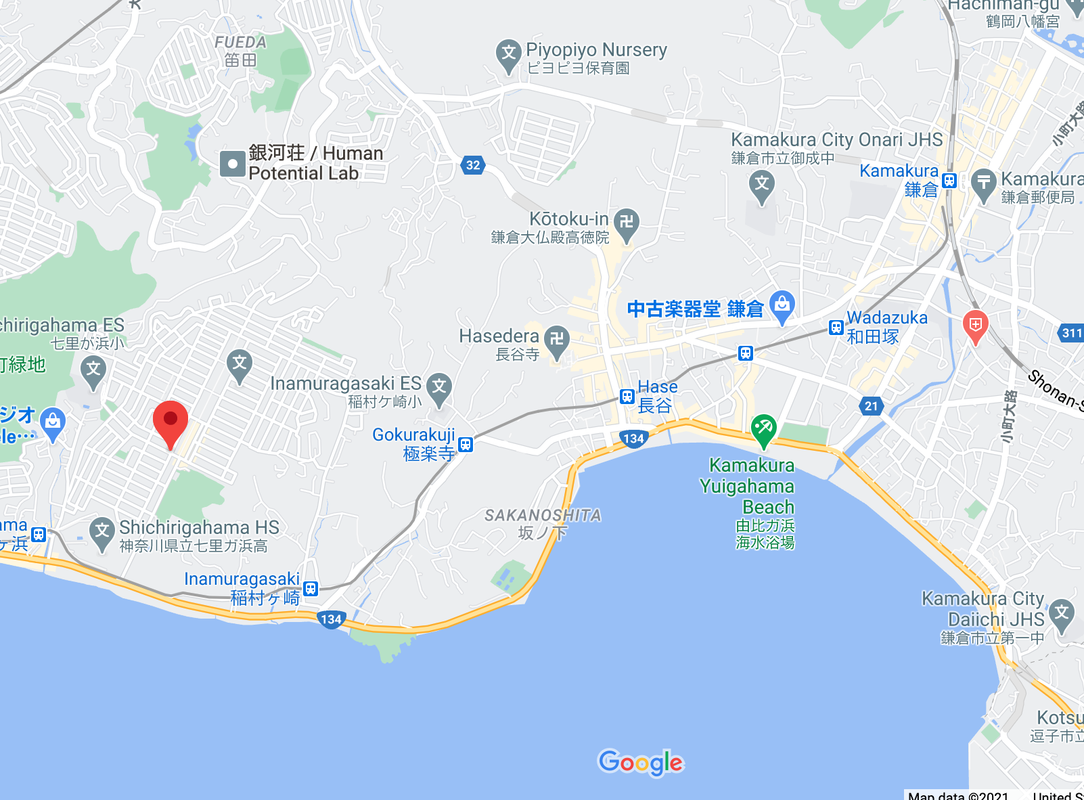

Had I know that I could indulge my love of music, coffee, old temples, and Japanese craftsmanship going to just one friendly shop I would have spent the entire weekend there! Quiet Village, located 6 stops from Kamakura's main railway station is in its own words "...a quirky place at the top of a hill in Shichirigahama" where the atmosphere lazy, the coffee is good, and the music fine. Now that's my kind of place. Best of all, there are lots of ukuleles at Quiet Village. Even better is that you'll find some exquisite handcrafted Japanese ukuleles that will be better than most you'll ever see. When we can all travel again be sure to visit Quiet Village, have a cup of Joe, and enjoy the instruments and the music. If you can't wait until then, visit them here. Then go there!

2 Comments

Shinji Takahashi is perhaps one of the best luthiers making ukuleles in Japan and this album is a fine indication of the type of work he does. He sells his instruments under the Seilen brand name and while not cheap, they are exquisite! Notice the craftsmanship. Notice the wood. Shinji’s FB posts are as often about the wood he finds as much as they are about the instruments he makes. Japan may just be the center of high end ukulele luthierie. I hope Shinji will take the next steps and make high-def sound recordings of the wonderful instruments he makes and improve the international distribution of his wonderful products. Bravo Maestro! Lately I’ve been thinking about the first wave of musicians that popularized Hawaiian music in Japan. Most were American-born Japanese nisei looking for somewhere they could fit in. It’s a sad story that spans the Pacific. It is a story that rarely gets talked about.

Recently I bought an old Victrola phonograph and have been buying old 78s from the first half of the 20th century so I can hear the music as it originally sounded. On Ebay I found a copy of “Sue City Sue” recorded in 1948 by Buckie Shirakata and his Aloha Hawaiians with Betty Inada on vocals. I learned about Buckie while researching an article I wrote for Ukulele Magazine and just had to have the recording. Although I can’t tell you why, in 1945 “Sue City Sue” was a hit for its author Dick Thomas and then successfully covered by Gene Autry, and Bing Crosby. It’s not a particularly catchy tune and the lyrics are pedestrian. By the time Buckie and Betty released it in ’48, “Sue City Sue" went through a cultural transformation. The Japanese lyrics paint a familiar picture: boy meets girl and a saucy bird sings “chu-chu-chu”. The rest is history. The Japanese version has nothing to do with Sioux City or Sue at least until after Buckie’s steel guitar solo when Betty sings “Sue City Sue” in her native English. That’s what I like so much about this recording. It’s bicultural. Buckie, best known for playing steel guitar not ukulele, fronted one of the most successful Hawaiian bands in Japan. Buckie, born and bred in Hawaii, arrived in Japan in 1933 at age 21 with a time on his hands and music in his heart. More to the point, there were few places that would hire a young Japanese-American. So he packed up his band and took a gap year with his Aloha Hawaiians. The band recorded two Hawaiian songs before returning to Hawaii to finish college. In 1937 Buckie returned to Japan, got married and settled in Tokyo. From then on his band was named “Buckie Shirakata and the Aloha Hawaiians”. Betty Inada the US-born daughter of Japanese immigrants a year younger than Buckie Shirakata, grew up in Scramento, California. She was beautiful, headstrong, and talented when she arrived in Japan, also in 1933. If there were few options open for Buckie, there were less available for Betty. In the 1930s headstrong young Japanese women generally weren’t appreciated. Now chances are good that Buckie and Betty’s paths would have crossed in ’33 but we’ll never know. It wasn’t until after the war that they collaborated on “Sue City Sue” and others. That generation of Japanese-Americans had it hard. They were viewed as neither Japanese nor American by either country. If they had stayed in the USA they would have been placed in relocation camps. But as fate would have it, both were in Japan when the Pacific War broke out and were forced to make a living singing forbidden foreign songs at a time when both countries questioned their allegiance. Buckie and Betty kept singing throughout the war years, Buckie slyly rebranding his Hawaiian tunes as “southern” Asian tunes using Japanese words. By the time “Sue City Sue” was released in Japan in ’48 Japanese wanted no more than to forget the recent horrors of the war and Betty and Buckie had a hit. They restarted their careers with mixed success. Buckie stayed in Japan, released multiple Hawaiian albums at a time when Japanese needed dreams of tropical, carefree south sea islands. During the war Betty married a Japanese film star who she later divorced. Betty remarried, moved to Los Angeles and returned only twice to Japan to perform her old songs. For a more detailed look at the fates of Japanese-Americans during the war years I recommend Midnight in Broad Daylight, by Pamela Rotner Sakamoto. The book traces the fortunes of the Fukuhara family before and after WWII. Some family members sent to Japan to complete their education became stuck there during the war years. One son fought for the Imperial Japanese Army while another remaining in the US was sent to a relocation camp and then enlisted in the US Army and returned to Japan in the occupying forces. Sadly, some family members died of radiation sickness after the bombing of Hiroshima. I've written before about how hobbies are a "thing" in Japan. If there's any doubt about that this family group proves I'm right. I haven't counted of all the videos they've posted on YouTube, but I'm guessing it's somewhere in the mid-two figures. Only a few of those have garnered more than a couple of dozen views, and yet this family is GOOD and they keep on posting!

The little I know about them is what's disclosed on their Ukulele Keiki YouTube channel "About" page, the sparce notes on their videos, and the odd bit here and there that I've heard said about them at the festivals they go to. Their daughter Moana (12) is a 7th grader, and their son Kanoa (10) is in 4th grade. I don't know who is doing the arrangements, but they are lovely! They perform well as an ensemble and while not exactly "professionals" they sure make a good go at it. I mean, just getting your kids to sit and practice is hard enough but to do it together as a family group, well that's admirable. What I like so much is that this family obviously spends a lot of time together playing and perfecting their performances and they seem to be doing it for no other reason than they like it! I like it too. Play on! I came of age during the singer songwriter era in the early 70s. James Taylor, Joni Mitchell, Gordon Lightfoot, Carole King, Laura Nyro... You get the idea. Matsutoya Yumi (aka Yumin, nee´ Arai Yumi) is a Japanese singer songwriter from the same era. She wrote some incredibly beautiful songs, many of which have been used by Studio Ghibli as soundtracks for its animated moves. In this video Yoshida Yuri covers Yumin's Sotsugyo Shashin ("Graduation Photo") beautifully. The tune sounds great on the uke and her vocals are spot on. Kind of like Dylan, Yumin isn't always the best singer of her own songs. But like Dylan what she writes is pure poetry. Read an English version here. You can hear the English version here. It's not a direct translation of the Japanese but it's close and maintains the spirit and feeling of the original. As with all translations, there's inevitably something that's lost. It's a shame that Americans don't listen to foreign music because Yumin would have been a great hit in the US. Visit her YouTube channel and let me know if you agree. Download words and chords for each version below.

I recently found a really great strap that allows players of vintage ukuleles to avoid drilling holes in their instruments. It’s the Mobius Strap designed and marketed by Tim Mullins. But before I get to why I think the Mobius Strap is so great, let me drag you along on my journey of discovery.  Genesis: Like many ukulele players, particularly those in Japan, I’m in love with vintage American ukuleles. I especially like vintage Martins. A few months ago I found a pristine 1950s Martin tenor uke which I have enjoyed playing ever since. Well, almost. I play mostly finger style and maybe I’m just uncoordinated, but I need a strap. I can't support the uke well enough with my left hand when I’m going up and down the neck switching between chords and notes. Yet my 50’s Martin was so pristine that it didn’t have any strap hardware leftover from a previous owner. That made me the unfortunate one who had to decide whether to deface my beautiful instrument by adding a strap. CRAP!

Confession:

As with most things in life once we reach a plateau where needs and wants are at an equilibrium, our needs increase. While I promise to be true to the Mobius Strap, wouldn’t it be great if it came in something other than basic black? Just sayin’ Tim… Scripture Reading: Faith, hope, love, abide these three; but the greatest is a perfect ukulele strap. Head on over to http://www.mobiusstrap.com for an un-hole-ly strap today. (Sorry, I couldn't resist.) Amateurs are Alive and Well in Japan!In Japan hobbies are a thing. A BIG THING!

It’s not long after you meet someone that you are inevitably asked: 趣味は? What’s your hobby? Here a hobby is like stamp collecting, something your weird uncle Harold did in the 1950s. Wanna see his stamp books? “NO!”, you quickly say. Besides, being an amateur anything just reeks of some juvenile preoccupation, right? Maybe because I’ve lived in Japan and have seen first-hand what true amateurism is, I don’t think so. In Japan, a hobby is an opportunity to do something simply for the love of it. We’ve forgotten how to do that here. The french root of the word amateur is amator, which means “lover” as in a lover of something. That meaning, however, often takes a backseat to the more condescending “One who does something without professional skill or ease.”, i.e., a hack. How often have we heard the expression “He’s just an amateur.” as in, “Don’t even bother, he’s not worth it!” I hereby loudly and forcefully OBJECT! There are many things that can and should be done even if the outcome is imperfect. There’s a tremendous amount of grace and learning that comes from the simple act of trying. Besides, it’s fun. Japanese don’t labor under the same stigma of amateurism that we Americans do. They take great pride in their hobbies and devote a tremendous amount of time, effort, personal reputation, and money into indulging their passions. Pick any hobby and you’ll find some of the best how-to books, magazines, videos, tapes, accessories, tools etc. available in Japan. I learned long ago that when you ask a Japanese about their hobby to beware. Personally, I often feel like a hack when compared to a Japanese amateur! While maybe not a “professional”, many Japanese hobbyists I know are darn near that level. They have diligently practiced their hobby for many years making slow yet incremental progress toward achieving hobby nirvana. It’s like that with the ukulele in Japan too. Instructional methods abound. How-to videos on YouTube are legion. Really good songbooks are everywhere. Japanese love, collect, and cherish expensive ukuleles from the US. They practice. They perform. Best of all, they love what they are doing. I don’t think American ukulele players are as hung up on being labeled amateurs as other hobbyists are. Perhaps we’ve grown a thick skin because we’re always derided whenever we pick up our small instruments. Or, maybe it’s just the unique joy that the ukulele brings. Whatever it is, I’m glad for it. Meanwhile, if you’re looking for Japanese songbooks, take a look here. Several years ago I stumbled across an article posted on the Internet titled Germans in Grass Skirts about how the humble Hawaiian uke saved German-American C.F. Martin’s bacon from getting fried in the Great Depression. I faithfully bookmarked the URL and when I recently thought to access it again it was gone. Such is life on the Internet. Whatever, I’m using that title as inspiration for this post about how the Japanese saved Martin's ukulele. In Germans in Grass Skirts the author described how by 1926 demand for Martin’s ukuleles far outstripped supply. According to Tom Walsh and John King’s excellent book The Martin Ukulele: The Little Instrument That Helped Create a Guitar Giant, in April of 1926 Martin’s Board of Directors decided to raise ukulele prices in the wake of strong demand noting “the reason for the increase is largely to provide money for enlargement and to provide a reserve for harder times.” Boy, did they ever call that one right! By 1929 uke sales were a third of their peak production level in 1925. Fortunately, the extra revenue from ukulele sales helped fund factory expansion and gave Martin a cushion to rest on during the Great Depression. After ukes surged again in the 1950s (thank you Arthur Godfrey), they fell again and by the late ‘60s C.F. Martin was making only a handful of ukes. 1965 was the last year of regular production after which ukuleles were produced only on special order. In 1994, ukulele production ceased altogether. Oddly, Martin was the victim of its own success. Between the 1907 and 1977 the company had produced over 190,000 ukuleles and used Martin ukes were cheaper than new instruments. A new style “0” cost $500 at retail but you could get a very good used Martin uke cheap at a flea market. No kidding! Just ask Jim Beloff… But not so fast… Kurosawa Gakki, Martin’s key Japanese distributor never got over the loss of the ukulele. Japanese are great collectors and, as we know, avid ukulele fans. Despite a depressed US market, Kurosawa felt there was still a market for Martin ukuleles in Japan. Chris Martin, however wasn’t so sure and beautifully tells the story in his “A Word from Chris Ukuleles” in minute 5:07. I would have loved to have been in that meeting when Chris produced several 5K prototypes to show Kurosawa’s executives. From the video its pretty clear that no one in Martin’s entourage spoke Japanese. In a typical meeting between Japanese and foreign visitors it is not unusual for the Japanese at key moments to break away from the main conversation and have an animated “chat” among themselves about what’s been said and much more. There’s nothing underhanded, they are just trying to gain consensus. If you speak Japanese as I do, it’s a great way to get a real-time feel for what your customers are thinking.

Since neither Chris Martin nor his International Sales Rep. spoke Japanese, they were floored when Kurosawa Gakki came back and met their $5,000 MSRP request and immediately ordered 50. That $250,000 order put Martin back in the ukulele business. For that amount, I’m sure even Chris Martin would don a kimono. I know I would! I recently fell down a rabbit hole…

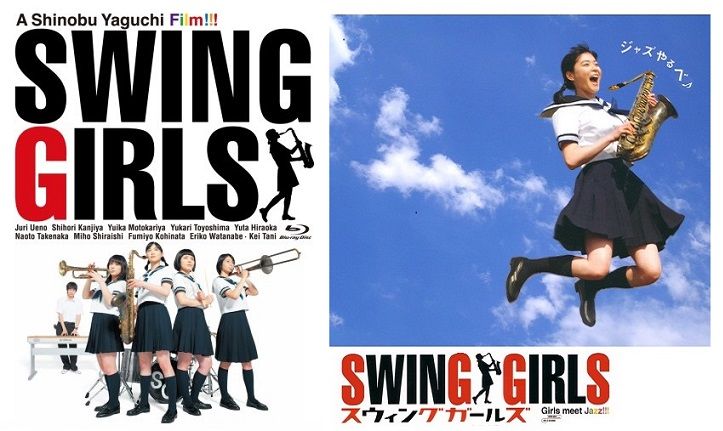

I started researching the origins of the ukulele in Japan, how it got there, who were the early stars , etc., and I learned something new which surprised me but it really shouldn’t have. Second generation Japanese-Americans (nisei), sons and daughters born and raised in Hawaii, brought the instrument back to Japan when they returned there in the 20s and 30s to complete their education. Yukihiko (Harry) Haida and his brother Katsuhiko both born in Hawaii of immigrant parents returned to Japan with a love for Hawaiian music and a lot of talent. Their Moana Glee Club recordings were well received and started the Japanese love for Hawaiian music that continues today. Then there’s Buckie Shirakata who arrived in Japan in the 30s and formed the Aloha Hawaiians. Buckie was quite prolific and made over 200 recordings, one of which was with Betty Inada, a Sacramento girl who returned to Japan to become a jazz singer. So here’s the thing… In the 20s and 30s life in America for most children of Japanese immigrants was like living on a tightrope and having to balance between the culture and traditions of your parents and of the place of your birth. Neither culture fully accepted you. In race conscious America it was hard for a Japanese (“J*ps”) to break into society regardless of talent and brains. Yet in Japan these Americans were looked at suspiciously and said to be bata-kusai- stinking of butter, a derogatory term for Western foreigners. As ambassadors of the mysterious and exotic Hawaii and the world of jazz, nisei had a cache in Japan that they didn’t have in the States. They were cool! They could also support themselves playing music at a time when there still was money to be made in that profession. Harry Haida and Buckie Shirakata married Japanese women and began to settle down. Betty Inada gained renown as a chanteuse in Tokyo nightclubs. Then the war happened. Like many Japanese who returned to Japan to complete their education or to work, after December 7, 1941, there was no going home and because they were not born in Japan, life for them was tough there too. “Foreign music” was banned. The Moana Glee Club became “The Southern Band” and the Aloha Hawaiians, “The Music Group”. I can only imagine how difficult it became to support oneself. I recently learned about the plight of the many Japanese-Americans stuck in wartime Japan by reading the book Midnight in Broad Daylight (Pamela Rotner Sakamoto) which chronicles the wartime experience of one family with children on both sides of the Pacific. One brother was interred and then fought for the US Army, another for the Japanese Imperial Army. A sister was in Hiroshima when the atomic bomb was dropped and later died of radiation sickness. All faced discrimination from every side. I’d love to hear Harry’s, Buckie’s, and Betty’s stories of how they coped during that time. After the war Occupied Japan needed the nisei entertainers to play for the US forces and many gladly did so. Being bi-cultural and often bilingual, the nisei were an ideal group to act as musical ambassadors. Soon a second Hawaiian boom fueled by Hawaiian nisei began to feed Japan’s insatiable curiosity for the exotic islands where the button-down, rigidly proper decorum of Japan was replaced by the flowered-shirt Aloha spirit. Hawaiian bands flourished in the 50s, 60s, and do so even today. All the while the ukulele has played a staring role in that drama, a role which would not have been possible without the many Japanese-American players: Herb Ohta, Roy Sakuma, Byron Yasui, Herb Ohta Jr., and most recently Jake Shimabukuro. I started this piece by mentioning the rabbit hole. It appears that there are numerous recordings of Japanese-Americans singing in Japanese and English for Japanese audiences that are still available for listening. Club Nisei covers the post-war period. On Soundcloud you can listen to a program in several hour-long installments. You can read about some of those recordings here. There are some interesting books too: Blue Nippon: Authenticating Jazz in Japan. E. Taylor Atkins Reminiscing in Swingtime: Japanese Americans in Popular American Music 1925 - 1960. George Yoshida Finally, head on over to UKULELEjapan.com (Artists Pages>Legends) and listen to Buckie Shirakata and Harry Haida. Back down the hole for me… Spoiler alert: this post has nothing to do with ukuleles, but if you're interested in Japan, Jazz, and Japanese culture, read on. I just finished watching Swing Girls, a 2004 Japanese film staring Ueno Juri. I really enjoyed it, even if there weren't any ukuleles. Swing Girls is what would happen if the Bad News Bears met your local jazz band. Predictable, but fun. The movie is set in Yamakawa High School in Yamagata Prefecture, deep in the northern backwaters of Japan. The girls are in remedial math class for the summer when they learn that the school's brass band has been sent off to play for the school baseball team without the customary bento boxes for lunch. The girls offer to deliver them so as to get out of class for the afternoon. They miss their train stop, have to walk back, fall in the mud, and manage to give the band food poisoning before they are roped into becoming the new band. Because there aren't enough of them to form a full band, after hearing a recording of Glen Miller's Moonlight Serenade they decide to become a jazz band. Reasonable, right? The girls face many obstacles, not the least of which is their complete and utter lack of musical training. But they persist. They manage to find a band director, conveniently their former math teacher, who despite his love of jazz and his own desire to play an instrument, is a total failure. At about that time the original band recuperates from their bout of food poisoning and resumes their duty cheering on the baseball team. Undeterred and now in love with jazz, the girls continue studying and eventually become good enough to enter a regional high school musical competition. Predictably, the forces of nature, their own self-doubt, and any number of minor disasters conspire against them but in the end they prevail. At about 16:30 in the above clip the girls make their debut at the regionals. I dare you to not smile when they launch into Louis Prima's Sing, Sing, Sing.

Everyone loves rooting for the underdog, especially the Japanese. Perseverance must be genetically encoded in Japanese DNA because they like nothing more than coming up against long odds. It really doesn't matter if they win or lose. It's persevering that matters most. Maybe that's why Japanese love the much maligned ukulele. Nothing says perseverance so well as a uke! Footnotes: 1) Only one of the 17 actresses who became the Swing Girls had any musical chops. They all learned their instruments well enough to at least play convincingly and after the movie was released held their "First and Last Concert" at the Tokyo JAL hotel in late December, 2004! 2) My Japanese is pretty good, but combine the heavy Tohoku dialect, teenage slang, and pouty girl-talk and I was often lost. 3) In reading some of the PR from the time the movie was released I learned the catch phrase was: 「ジャズやるべ」which translates roughly to "Let's do some jazz y'all!". Understand my problem now? I'm glad I persevered! |

AuthorI'm an amateur ukulele player who happens to be fluent in Japanese. I hope that I can inspire you to learn more about the ukulele, Japan, or better yet, BOTH! Archives

February 2021

Categories |

||||||||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed